This post is the second in a series on Community Engagement. You can read the first post here.

In our experience working on cultural and educational projects, we have found time and time again that community engagement can be an enriching part of the design process and can lead to unanticipated, wonderful outcomes which elevate a new building immediately to be a beloved community asset.

Community member involvement and interaction with the design team can set a project up for success: building trust and uniting participants around common goals, creating a sense of transparency and inclusivity, establishing and verifying the project’s programmatic components, and articulating priorities which allow for in-depth, objective evaluations of options.

When integrated into early planning, strategic community engagement has the potential to influence the aesthetic, fiscal, functional, programmatic, and organizational trajectories of a project. To illustrate this possibility, we will delve briefly into two projects which solicited community member involvement at the project onset to define the project, determine priorities, and aid site selection: Devil’s Lake State Park Interpretive Education Center and a Campus Master Plan for a private Maryland K-12 institution.

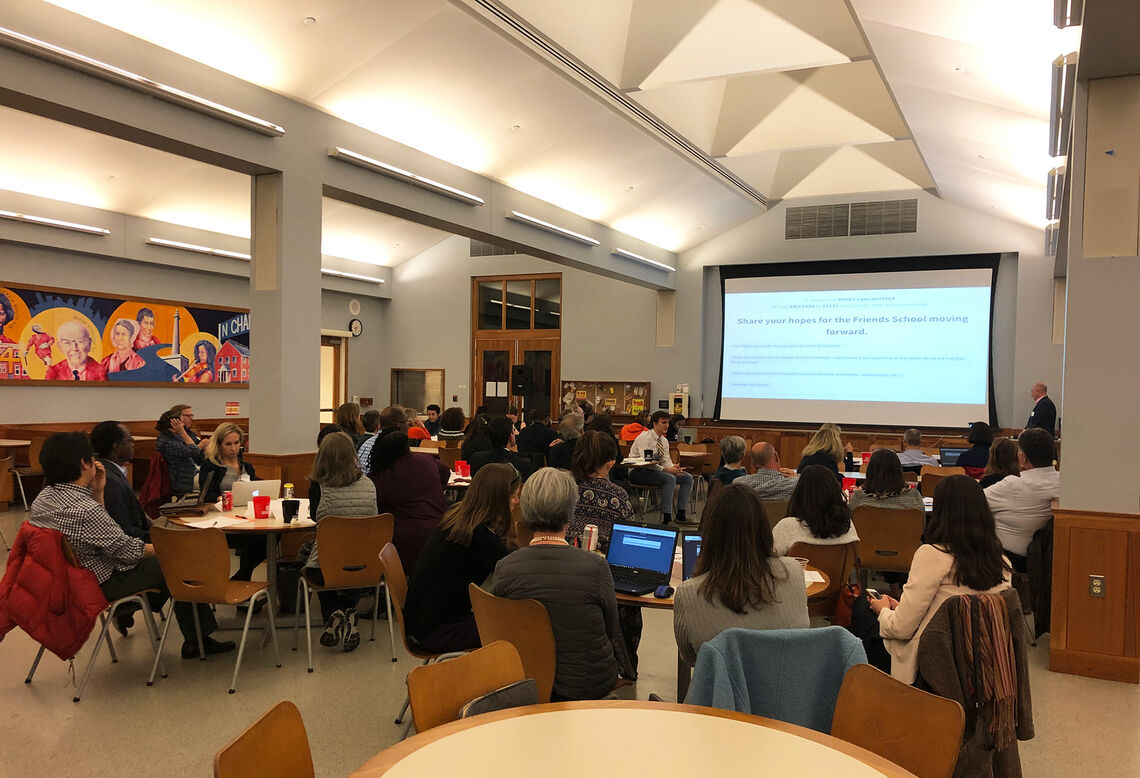

Let’s take a look at the Private K-12 Institution Campus Master Plan design process first, which involved a diverse and dedicated school community eager to engage in the process. GWWO, together with the school’s Steering Committee, utilized two primary tools for collecting information from the community: an online survey and an in-person stakeholder workshop. The online survey was distributed to students, parents, faculty, staff, select alumni, the Board of Trustees, and other friends of the school. It asked broad questions for all respondents to answer, and then offered respondents the opportunity to answer targeted questions on individual buildings and campus features. Over 200 online survey participants provided thoughtful responses which identified specific topics to focus on during the in-person stakeholder workshop of approximately 70 participants. There, GWWO used live polling to collect and display responses in real time with the assembly. Small and large group discussions further fleshed out important considerations for the campus and community. The data collected via these two engagement processes generated the Guiding Principles, a set of seven overarching goals which captured wide breadths of community values, essential features, and critical objectives identified for the school’s future success. These Guiding Principles became fundamental to the Campus Master Plan, and acted as tools to develop, optimize, and evaluate the various options and potential projects. Moving forward, the school intends to use the Guiding Principles to prioritize projects and guide future capital planning decision-making for campus.

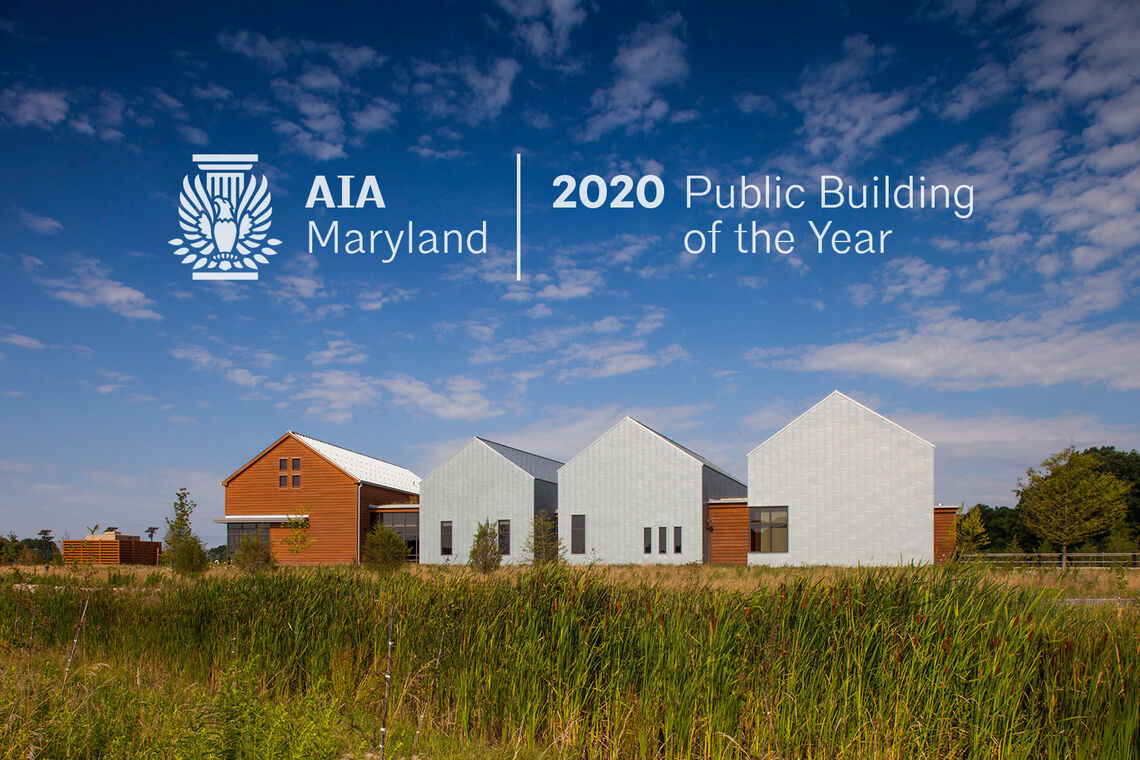

For Devil’s Lake State Park Educational/Interpretive Center, GWWO used engagement strategies with two specific groups: the community at-large and the project stakeholders. For the first and larger group, ideas and comments were gathered through two main avenues: community meetings and a project-specific website created by the design team. The website served—and continues to serve—as a place to provide project information and updates throughout the life of the project until construction is complete, and it also hosted an online survey for the submission of community member feedback. Both the community meeting discussions and online survey results informed and validated the site selection process and provided invaluable understanding of the community’s desires for the new center.

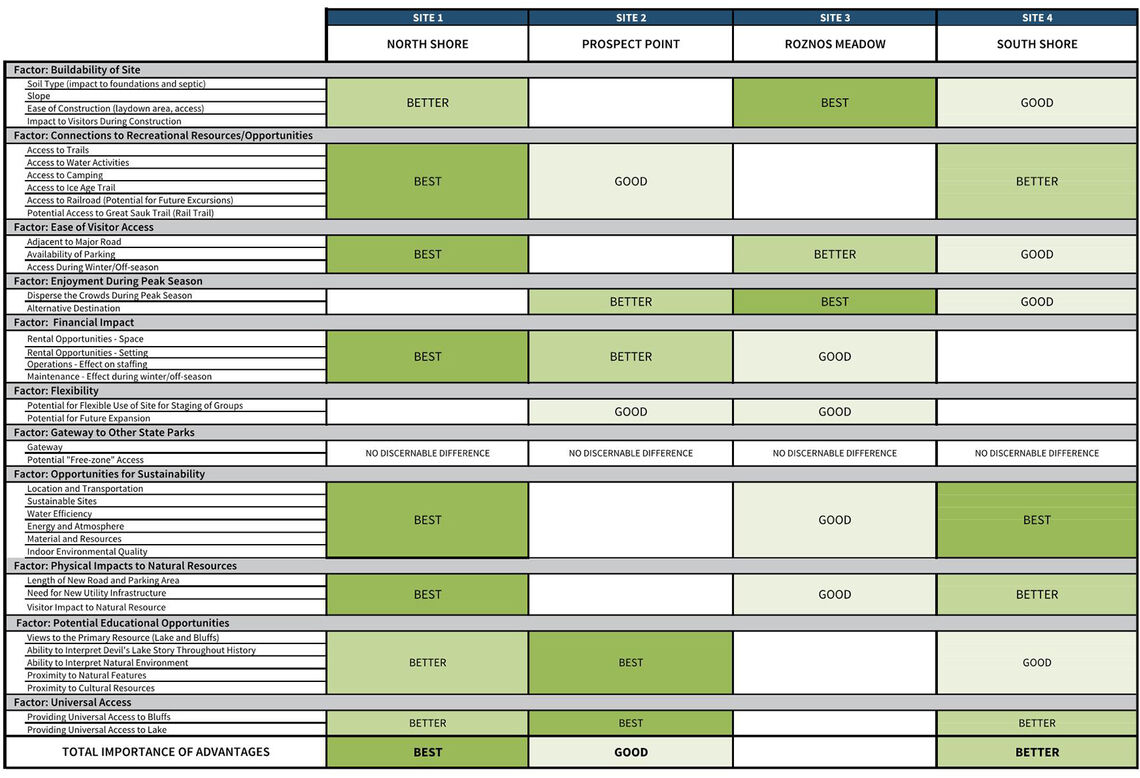

For the project stakeholders—Friends of Devil’s Lake State Park, Devil’s Lake State Park Staff, Devil’s Lake Concessions Corporation, and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources—we also facilitated an in-person Choosing By Advantages decision making process to objectively analyze potential building sites throughout the State Park. This process was instrumental in comparing eight vastly different, and in some cases controversial, sites. Allowing the stakeholders to synthesize input and concerns from the community and their own groups, the process both determined the most advantageous site for the proposed Educational/Interpretive Center and documented that decision for interested parties to understand.

Although it does often represent additional time and effort within a project’s development, we have found that community engagement—particularly when it starts early and includes a feedback loop for continued sharing of information—creates a positive sense of inclusivity and transparency. In both examples discussed above, the input collected from the community was essential in creating a framework for the design team to use in evaluating and optimizing options: truly a win-win scenario!